Optimism has long been a uniquely American trait. It defines who we are. We are a nation of people who believe tomorrow will be better than today. It is why our forefathers and mothers risked long ocean voyages in search of a new world, why settlers in wagons ventured ever westward and why immigrants continue to come here by any means possible, by plane or make-shift raft from Cuba. (As a Pakistani born son of Irish immigrants, it is why I am here today.)

Our ingrained sense of optimism was set in motion by our founding story, fueled by generations of immigrants and reinforced by years of abundance and success.

Lately, though, I've come to wonder if our definition of optimism, or more pointedly our underlying motivation, has changed over the past decade, perhaps not in a good way.

American optimism was always an extension of our "can do" spirit. Anything was possible if we worked hard enough to make it happen. Our optimism sprang from hard work, not hope. We knew tomorrow could be better for us and our children if we rolled up our sleeves.

Recently, however, optimism evolved to become an entitlement, no longer an earned reward. We bought houses bigger than we could afford because we had every reason to believe we would get another raise or that our portfolio would continue to grow. We used magic money -- a.k.a., home equity loans -- to buy the muscular SUVs we coveted. We didn't have to work any harder. Good things just happened.

While the current recession has shaken our confidence, recent polls suggest that President Obama is inspiring us to find reasons to be hopeful once again.

I am hopeful the current "cleansing" process will bring us back to the true definition of American optimism. Tomorrow will be better than today, but only if we roll up our sleeves and earn it.

How the Handover Begins

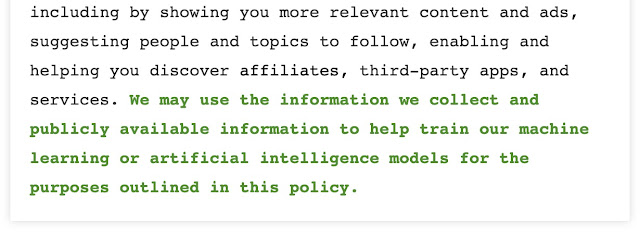

Today’s New York Times features an article that pulls back the curtain on how the AI handover is getting underway, how Google, Meta, X, et a...

-

I don't know who authored this quote, but I found it in this video of a presentation Yves Behar gave at TED about the need for design t...

-

I was thinking the other day about the DNA of premium brands . One thing is certain -- it's a relative idea. For example, Hyatt is...

-

As a passionate Giants fan it is safe to say that I had a good time yesterday. But as an advertising professional I felt a bit underwhelmed ...